- Home

- Episode

- Get Matched

- New Mexico Artists

- Art + Music

- Art + New Tech

- Analog Photography

- Being a Full-time Artist, Stone Sculptor

- Creativity & Computing

- Creator, Curator + Art Dealer

- Creativity, Curiosity and Chemistry

- Designing Sets for the Film Industry

- Finding Joy

- Goldleaf Framemakers Studio Tour

- Handcrafted Jewelry + Furniture

- Hot Air Balloon Adventures

- Illustration Watercolor Painting

- Making a Living as a Sculptor

- Music and Art Law

- Modern Folk Art

- Oil Painting & Inspiration and Other adventures

- Painting, Behind the Scenes Studio Tour

- Talking Music

- Speed Portraiture | Essential Workers Project

- The Free Range Buddhas

- Photography

- Analog Photography

- Banter + INTRO!

- Cyanotype Photography and Bird Houses

- Photography, Hip Hop + Culture

- Polaroid Photos + Publishing

- Speed Portraiture | Essential Workers Project

- Telling a Story with Filmmaker + Photographer

- Film Photography Vs. Digital + Shooting from the Hip

- Exploring Culture Through the Lens

- Painting + Drawing

- Music

- Art + Science

- Sculpture

- Tattoos

- Theater

- Shorts

- One Celebration | Knowledge Drop!

- Studio Tours

- In the Wild

- SOCIAL HOUR – Art, Music, Copyright & other stories …

- Artists

- New Mexico Artists

- Jessie Baca

- Cody Brothers

- Marie Blessing

- Michael Burt Jr

- Dorielle Caimi

- Eric Cousineau

- Tim Church

- Josh Gallegos

- Stephen Guerin

- Danny Hart

- David Horowitz

- Laird Hovland

- Francesca Jozette

- Talia Kosh

- Roland Van Loon

- Diego Mesones

- Taura C.C Rivera

- Greg Robertson

- Michael Rohner

- David Scheinbaum

- Zac Scheinbaum

- Ray A. Valdez

- Croix Williamson

- Alberto Zalma

- Photography

- Music

- Painting + Drawing

- Art + Science

- Sculpture

- Tattoos

- Theater

- New Mexico Artists

- Videos

- Transcriptions

- Photos

- About

- Opportunities

- Members

- Contact

- Home

- Episode

- Get Matched

- New Mexico Artists

- Art + Music

- Art + New Tech

- Analog Photography

- Being a Full-time Artist, Stone Sculptor

- Creativity & Computing

- Creator, Curator + Art Dealer

- Creativity, Curiosity and Chemistry

- Designing Sets for the Film Industry

- Finding Joy

- Goldleaf Framemakers Studio Tour

- Handcrafted Jewelry + Furniture

- Hot Air Balloon Adventures

- Illustration Watercolor Painting

- Making a Living as a Sculptor

- Music and Art Law

- Modern Folk Art

- Oil Painting & Inspiration and Other adventures

- Painting, Behind the Scenes Studio Tour

- Talking Music

- Speed Portraiture | Essential Workers Project

- The Free Range Buddhas

- Photography

- Analog Photography

- Banter + INTRO!

- Cyanotype Photography and Bird Houses

- Photography, Hip Hop + Culture

- Polaroid Photos + Publishing

- Speed Portraiture | Essential Workers Project

- Telling a Story with Filmmaker + Photographer

- Film Photography Vs. Digital + Shooting from the Hip

- Exploring Culture Through the Lens

- Painting + Drawing

- Music

- Art + Science

- Sculpture

- Tattoos

- Theater

- Shorts

- One Celebration | Knowledge Drop!

- Studio Tours

- In the Wild

- SOCIAL HOUR – Art, Music, Copyright & other stories …

- Artists

- New Mexico Artists

- Jessie Baca

- Cody Brothers

- Marie Blessing

- Michael Burt Jr

- Dorielle Caimi

- Eric Cousineau

- Tim Church

- Josh Gallegos

- Stephen Guerin

- Danny Hart

- David Horowitz

- Laird Hovland

- Francesca Jozette

- Talia Kosh

- Roland Van Loon

- Diego Mesones

- Taura C.C Rivera

- Greg Robertson

- Michael Rohner

- David Scheinbaum

- Zac Scheinbaum

- Ray A. Valdez

- Croix Williamson

- Alberto Zalma

- Photography

- Music

- Painting + Drawing

- Art + Science

- Sculpture

- Tattoos

- Theater

- New Mexico Artists

- Videos

- Transcriptions

- Photos

- About

- Opportunities

- Members

- Contact

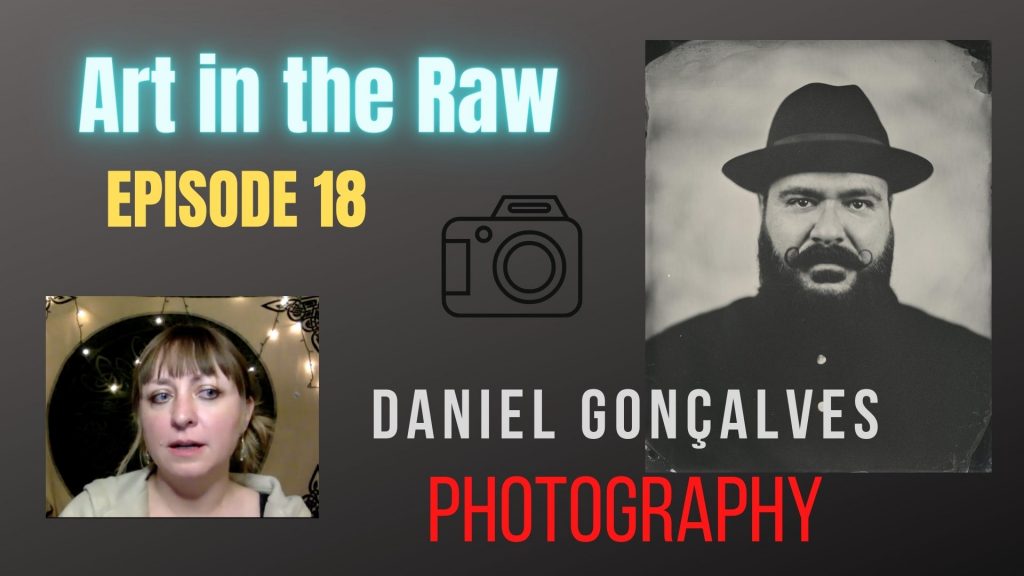

Transcription DANIEL GONÇALVES | Photography: Exploring Culture Through the Lens

Transcription

Anne Kelly (00:13):

This is Art in the Raw. I’m your host and Kelly. Today. We are here with my friend, Daniel. Daniel is a photographer and I cannot pronounce his last name. So I’m going to let him do that for us. Thank you for joining us today. Daniel.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (00:31):

Welcome going, dissolve this Americanized version.

Anne Kelly (00:37):

Yeah. I was going to try that, but I knew I was gonna, I was going to butcher it, so we just thought we’d let you go for it.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (00:44):

You would not be the first I’ve gotten all kinds of stuff. My French teacher, she used to call me, gone, gone clays. For some reason, people call me David as well. I don’t know why I don’t get that. Even on my signature. There’ll be like signed Daniel can all those. And I’ll be like, Hey David, what’s David. So that’s my alter ego. And then I started like, okay, I’m gonna make a cheat sheets on my business card. On the other side, I have like, you know, sounds like a mask has got that little, little squiggle line, which makes you sound like a mess disobedient. And then, um, someone was like, you know, have to be pronunciate. I’m like, I got this. So I pulled it out. I’m like, here you go. You can keep it. And they’re like looking at it, like, okay, I get it on slaves. So, um, yeah, it got a new mispronunciation. Now

Anne Kelly (01:37):

Your name, your last name is Portuguese. And you are from Canada or Canada is where you were born.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (01:46):

I was born in Toronto, in little Portugal, uh, where my parents had a little Portuguese supermarket. So it was very ingrained in Ricky’s community. There. I kind of, at times more important to you from those growing up, it was just like, I mean, people, you could live your whole life in Toronto, not speak a word of English as a support to express.

Anne Kelly (02:04):

I did not know that. And you’re in LA now

DANIEL GONÇALVES (02:07):

LA orange county, but yeah, I say LA because people don’t know where Irvine is or like, or hoop LA. Yes. Okay. Got it.

Anne Kelly (02:18):

Like, this is my last name and I live in LA yes.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (02:24):

On slaves and LA.

Anne Kelly (02:27):

So, so your family owned those, what was like a little supermarket, right? Or,

DANIEL GONÇALVES (02:33):

Yeah, that’s the one that would teach it market. It felt big growing up. It was pretty small. It was like a little mom and pop shop. And we had winded up like bind a little bakery across the street, the port to the bakery there.

Anne Kelly (02:43):

So within your photography, you’ve always been interested in identity and culture and American culture is something that’s popped up repeatedly. And so we see a bit that, uh, within two of the bodies of work that are featured on your website, and we’re also going to talk a little bit about a new body of work. Uh, that’s not yet on your website. So that’s kind of exciting. Do you want to go into, um, kind of the connections between all of those things? A little bit?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (03:21):

Sure. Yeah. So like, like I was saying, I was always kind of like fascinated with America growing up. I felt like this place of opportunity and I don’t know it was a Portuguese. I was trying to run away from this identity of being poor growing up. Cause it’s like, everybody in your school is Portuguese and there wasn’t that smell Serbians for lunch and

Anne Kelly (03:39):

Sounds super cool.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (03:40):

But when you’re a kid you’re just stupid. You don’t really think about like how special the situation is that you’re in and how unique it is. Um, but you always want what you can’t have. So anyway, like that’s always kind of stuck with me, like, what does it mean to be American? Like what is America like all these different things and how is it cool to be American? What is it like, do you talk differently? Do you, what is it? Right. So that’s, what’s been kind of fascination of what it means to be American and then kind of coming in American citizen to kind of have to go through that transformation. And um, yeah. And the officer just kind of like this triple identity of like being Canadian, Portuguese and American now. Cause it’s like when they go to Portugal and the Canadian, when I’m in Canada, I’m the American I’m in America and the Canadian.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (04:27):

So it’s like, I don’t really belong anywhere, which is always kind of awkward. And I always get blamed for things. It’s like, you know, I’m a Portugal, it’s cold here. It’s your fault because you’re Canadian, you know, when I go to Canada, like, you know, Bush was president at the time and you know, my friends would give me crap. They’d be like, it’s your fault know, look, look with this more on. So I’m like, I can’t even vote, man. And he can’t blame me for this. It’s like, it’s your country. I’m like, I’m not even a citizen. You can’t blame me for this. So I don’t know. Just kind of, and also kind of how, when you, like, when my parents came from Portugal to Canada, how you kind of brought your culture with you and have a supermarket, but it changes. Cause then it’s like, you got your con your American stuff, Canadian stuff, north American stuff, you have your Portuguese kind of stuff. People are coming in that are from where you’re from. It’s just kinda how things kind of morph. You only bring things in, like when we came to America, I actually opened up a bakery in Florida, much smaller Portuguese population. Toronto’s got a huge population. So now you’re like, okay, well I need a catered to this community, but it’s a tiny community. So how do I cater to the American pallet and introduce them to something that they’ve never heard of and also can give them like kind of American names so that it makes sense.

Anne Kelly (05:38):

Yeah. So it’s kind of, um, kind of exotic, but you can relate to it as well.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (05:44):

Yeah. It’s like Portuguese cookie.

Anne Kelly (05:49):

That sounds exciting.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (05:52):

It’s not, yeah.

Anne Kelly (05:54):

So you’ve always kind of used photography. It seems like to explore things that, that you’re curious about. But what I don’t know is when you started making photographs, how you got into photography, what, what that story

DANIEL GONÇALVES (06:11):

I’ve always loved photography. It’s always been kind of like this weird passion for me. I don’t know why I wasn’t like the family documentary in, we sound like a big VHS camera that weighed like 30 pounds. I would always be carrying it around, like in grade school. I was, that was so cool. Um, image civilization was like this huge like lens. I would like move inside of it. It was like a big square thing. I was like, this is so compact. Look at it. It’s like a big boom. And um, but I used to love it. And like, uh, in grade eight I was really into it. And like at the time, my best friend, Victor, we had done like a school project on it. And it did really well. And we were like one little like the little regional award and stuff for project of the year. And I was really into, it were developing super sketchy, developing photos on my parents’ basement or on the supermarket’s basement. And we didn’t even know what we’re doing. I think we like were visiting like processes that we didn’t realize we were using like projectors. So like we couldn’t figure out how to develop this. So we were like, just sear the images onto paper for like two hours and then bring it out and just like, it would eventually just become a image without any chemicals. I don’t even know where all that stuff is, but anyway.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (07:16):

Right. Exactly. And I loved it. And my mom smart woman that she is in Portuguese, she is, I wanted to get a, um, an SLR camera, which my friend, Victor got one for his birthday or Christmas or whatever it was my mom’s like, you’re going to medical school, no way. You’re not going to get a camera. So I’m sorry, I didn’t get a camera. So I always have like a little point and shoot, but it was always kind of like this like passion. And then when I was in college, I, um, secretly bought a camera. But when you about like my first, uh, some sketchy camera dude, like near USF was like, yeah, come over to my apartment. I’ll sell you a camera. And I was like, okay.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (07:57):

And um, yeah, about like a little Olympus, it was on 10 love that the thing was like a 50 millimeter, like 1.8 lens on it. And he just started shooting pictures and like, go on AOL and post like ads, like model portfolios, like, you know, cause I just wanted to like shoot stuff and then like, you know, like 10 bucks or something. And then like I’d saved up a little bit of money, but my first and larger and then like set up that up and then would just experiment with stuff in my parents’ basement when they go home for the summer. And then all my stuff, all my old, black and white like lab stuff. I don’t know where it ends. It’s in some dumpster somewhere. My mom like emptied out the basement and everything, all my gear, everything. I was like what to put the pictures, like what pictures.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (08:46):

And then more seriously, um, when things started to change in like in 2008, I started getting a bit more interested in that. Cause at the time I was running a bakery, I had a restaurant that was a, it was a real estate. I was the mortgage broker because all this different stuff and the market was collapsing around me. And then just like, I don’t know. And at the time Maggie and I had just gotten married and she was like, what would you do if you didn’t care about money? Like what would be the one thing you would do like photography, but how the hell do you make money photography? I’m still trying to work that out. But that was like the thing that I’ve always been passionate about. That’s something that’s kind of like always stuck with me.

Anne Kelly (09:25):

That was that probably everybody should ask themselves. What, what would you, you know, what do you really want to do if, if money is not a factor.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (09:34):

Yeah. And like, what else can you do that gets into like people’s lives in an intimate way? Like, I guess it could be first responders or something like ambulance dude. But I mean just if you’re curious about something, it’s like, you’ve got this little magic box and you can go into their lives and ask some questions that you’d be normally too afraid to ask. And I don’t think you get to like kind of really see people and listen to them and understand them. And I don’t know. It’s really cool,

Anne Kelly (10:03):

But, but what an awesome supportive wife that you have to ask that question at all?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (10:10):

Yeah. She’s awesome. And she’s quite artistic too. She does all kinds of cool stuff. She does. She plays it down, but she’s like, it does a little paintings and stuff and she’s cool. Oh, that’s cool. And that’s sort of question, question two. I’m like I’ve, I’ve kind of pushed her all along to them. Like when we met, I was like kind of the more successful one. She was kind of still doing other PhD stuff, then I’m like, well, what makes you happy? Because at the time she was in academia and she was just like burnt out, just stressed out. And then somehow she kind of found her path too. But, um, yeah, it’s all kind of a path it’s like, I think when I was younger, I thought, well, if you pick this one thing, you can do it. And then it’s like, hasn’t worked that way at all. It’s like, you kind of pick up one thing and then so like then you pivot and do something else,

Anne Kelly (10:52):

Florida and opening a bakery and that, and then here you are now. And it’s um, like, like I tend to say it’s, it’s all connected. So I was, I was, um, looking at your website this morning and I was rewriting your artist’s statement. And, um, there was something that caught my attention that I really liked, which you had mentioned the intersection of masculinity and vulnerability. And then I was just also curious how it kind of manifested in your work.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (11:25):

I just kinda noticed like when I’m like, you know, when you first start shooting, you just kind of like doing stuff and you don’t really know what you’re doing. You kind of process it later as you kind of like have some time to it’s a development to start new projects, start noticing trends. So I’m like, I keep on like quarterbacking the things that are like super hyper-masculine or like the topics are, and that are kind of like, but they’re all kind of leave the people that are in it very as well. So it’s kind of like this, like pounding your chest thing, like guns or bull fighting or whatever. And then it’s like, it’s like, these are all things that can kill you. And like the perceived like safety of them or the procedure bottle of it versus like the reality of it as well.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (12:07):

I don’t know. I kind of found that. And then it’s like, well, how about the women? It’s like, I think it’s everything. I think men and women both have masculine family inside of them randomly, whoever it is. I mean, we all kind of go through different ebbs and flows of it. You know, sometimes we cry. Sometimes we yell, sometimes we do whatever, but it’s all kind of maybe it’s testosterone, estrogen, whatever it is. But it’s just kind of, it’s interesting. It’s like a lot of these people that are really tough or that, you know, I was initially afraid of like, you find this kind of tender side to them at some point, and it seems to be a common thread.

Anne Kelly (12:37):

And when you start interacting with people, which is kind of a natural part of your, your photographic process in being able to interact with people in a different way where you may be kind of get to get below the surface a little bit more or where maybe you’re photographing somebody who seems a little bit threatening, but you’re interacting with them and you’re kind of going, okay, this is who this person is. And this is why they’re doing that.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (13:04):

It’s funny because I’m quite neutral. I think back to my wife makes fun of me a lot. She was like, you really are neutral. You really can never like make a decision. You’re just kind of like the middle, like with people. I always think of people as like everyone starts off good. So somebody does something that I perceive as bad. It’s like, is that person, does that make that person bad? Like why, why? Right. Like why do they do that? Or why does it look at it and doing something bad? So it’s like, is it just the perception of what people say about that person, whatever. It’s just like, I want to kind of like get in there and try to understand who that person is. It’s like, is it just because we came up from different backgrounds? Is it because we have different religions? Is it because we come with different parents? It’s like, maybe it’s a lack of education or actually I’m not educated on something or whatever. Right. So it’s kind of, um, I don’t know. It’s just kind of about understanding that.

Anne Kelly (13:54):

Yeah. And I actually, I think that makes a lot of friends in, in spending some time with your work. I, I think I can actually see that you’re approaching people kind of with that neutral perspective, maybe there are people you don’t, you didn’t know, you probably wouldn’t have known if you weren’t photographing them. Right. And I think just interacting with people kind of, without that, um, initial perceived judgment, this is what this person, I mean, it’s, it’s a very honest approach to part of your photographing them. It’s kind of figuring who is this person? What are they about? And you’re not entering with that preconceived notion.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (14:40):

You can’t really,

Anne Kelly (14:41):

I mean, there’s maybe

DANIEL GONÇALVES (14:42):

I don’t know how I feel about the person, but I understand my feelings in terms of fear, like fear is real. Right. So if I see someone with the gun, for example, that’s, I’m fearful towards that. I’m like, is this person in the army? And my brain is automatically firing off, like this person that wants to hurt somebody. It’s like, so that’s what I’m coming in with it. Right. And then it’s like, the more you get to know other people and your sound like what the motivations are or whatever, I’m like, I’m an idiot. Why would I think that this person would want to just harm me just because they could, or, or what

Anne Kelly (15:15):

About the guns? There’s a photographic project about that. And, um, you had kind of an interesting childhood story surrounding that.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (15:25):

So we have this Portuguese supermarket and I wasn’t in the store at the time I was upstairs where we lived, but my mother and sister were actually held up at gunpoint when I was probably grade seven grade eight. So my sister’s probably grade five grade six, and we’re support teas that were held up in port to use. The two did not hold up in English. So they actually, like my mom thought it was a carnival tread and grabbing his masks, federal spending the Portuguese carnival and out of the guy. And he said, I’m important to use this. Isn’t a joke. It’s an assault. And grabbed her and threw her on the ground from my mom’s handicap. And um, and then when he threw on the ground, she, he kinda like, he was like, oh crap. Like just the ports using them as like, I just wrote like somebody’s mom on the ground and basically this handicap.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (16:09):

And when they went over to like hesitate, my mom just grabbed onto whatever she could grab onto, which were his man parts. And, um, as he was like trying to pull her weight with his man parts, um, and y’all think the guy that was at the door had the gun said, let go, or I’ll kill your daughter because my sister was there. So it was like, my sister was like traumatized for quite a while after that. And we all worker and these guys were never caught. Right. And they were part of our community, obviously. So more in Florida on vacation. My mom went to Kmart and see about this BB gun, like this $10 BB gun. We tried, it didn’t even work, but we brought it back to Canada, which I found out that BB guns are actually illegal in Canada recently, which go figure she would have this gun.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (16:54):

And she’d be like, you know, showing it off to people being like, you know, we’ve got this gun, so don’t mess with us. And I’m like, you got this thing and it has this power. It’s actually protecting us in some way. Cause people think we have a gun, but we don’t really have a gun. So it’s like, if somebody comes in and she pulls this thing out, it’s like, you’re going to get killed. So I was kind of like against like that vulnerability and that masculinity or that power of vulnerability. It’s like, you have this gun that you think will protect you, but it’s like in the end that might get you killed because if people are hanging out and it doesn’t work and it’s a BB gun, which just can’t do anything, I don’t know. That’s kind of what stuck with me. And then, um, when we moved to Texas, I saw were one of them at the dinner. We’re in Dallas, really much part of the town. And these two gentlemen are walking around with, at the time, we didn’t know what they were, but they were air fifteens. And I was like, this is weird. I had my little camera, took a picture. I’m like, I think they’re about to kill people. I’m not really sure what’s happening. But they were part of a gun writes group called open carry Texas. So it’s kind of like my entryway into that. And then

Anne Kelly (17:53):

That turned into a photographic project.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (17:57):

Right. So at the time it was actually like, I just want to know who these people are. So I want to ask them some questions, like, cause I’m threatened that I’m feeling certain things and I’ve never seen the gun like that ever in my life, like only on TV. So one over and then talking to them, I’m like, okay, they don’t look at the gun, kill someone or hurt me in any way, shape or form. Let me talk to them. And then I’m like, oh, these are all right, dudes. Like, look at someone, I’d be friends with whatever. And they’re like, yeah, come up to a rally and check it out. Whatever we can ask this question, if you want whatever. I’m like, okay, cool. Like, and then I’m like, I can come take pictures. I’m Canadian. I don’t really know anything about guns. I’m terrified of, you can spend some time. And it’s like, I think if you’re coming at it from the point of understanding, they’re always open. I mean, people are always open to explain their stance and their position. They’re going to feel good. Being judged in some way, especially afraid Canadians. I don’t know. It’s kind of weird.

Anne Kelly (18:50):

Yeah. And then you also have another project about Elvis.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (18:57):

Yup. Elvis. I was turning 40 and I’m like, wow, this person who died 40 years ago, you know, the year I was born, it still has like this lasting pull across people all over the world, across people that weren’t born when he was alive. Like, how does this, what is that? Like, how, how can you still be sort of trapped into something where it becomes part of your life, where it’s like, you’ve got their image tattooed onto your skin or, you know, you travel the world. Like you’re, you, you save up to go to all those festivals. That’s your travel, you know, thing. That’s what you do every five years, you get to go to Memphis or it’s a Kroll or wherever. It’s like some Elvis festival or where you take on their identity and you become Elvis tribute artists where, you know, it’s kind of like that whole thing where you kind of take on this persona of this person, but you make it your own.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (19:47):

And that’s, and it’s like all the tribute artists, like they all have their own things. They have their own databases. It’s not like they’re not a replica of all of us. They’re their own thing. They’re the only artists. It’s kind of interesting. It’s like, but again, it’s like that. Why? Like, what is that? And I’ll get a really fresh sort of peace with it because it’s like, I get, oh, he’s such a beautiful man or he’s thinks so well, it was just like such a giving, press, whatever you get, all these like generic answers on like, come on man. Like, but you’ve been coming to Memphis like for the past 20 years, every single year. Right? Like you got tattoos of him, like you’re crying. Like, come on, there’s gotta be more than, so I started asking people as a way to kind of get a little bit deeper to write, let herself. So I’d be like, Hey, if you can read all this a letter and you need to absolutely read it, what would you say? Oh my God. I don’t know. I’m like, okay, well, if you don’t mind, I’m doing this project and I want to understand, and I want the shirt eventually. Can I give you this notebook? Go take as much time as you need everybody to all of this, a letter that he’s going to read. So it just started clicking all these different letters from different people. Are you still

Anne Kelly (20:47):

Working on that

DANIEL GONÇALVES (20:48):

A little bit? I think I’m done. That’s like what? The, the gun thing it’s like, once I got my answer, it’s like with the gun thing, it’s like, okay, it’s great. As to off neutral, ended up neutral spirit a bit, but it’s great. You know, uh, respect people’s rights if they’re not breaking the law. It’s like the eldest the same. It’s like, uh, went, uh, for the 39th anniversary, 40th and 41st anniversary met a lot of beautiful people. I’m like came out of it. Not really understanding it again. It’s like, there’s no right answer. It’s like, it’s different from everyone for everyone. Again, it’s like, you know, some people it’s for the music, some people do for the rockabilly culture cause they’ve cool tattoos and cool hair or whatever. And other people do it because they’re connected to another time, whether it’s family, you know, memories of watching Elvis with the grandmother, or I don’t know, just kind of like a different time in America where it was a little bit less complicated, you know, you didn’t have cell phones and Instagram and whatever.

Anne Kelly (21:45):

Yeah. And so now you are working on a project about both fighting, but specifically bull fighting in LA. Is that, do I have that right?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (22:00):

It’s a California. Um, so it’s bloodless, Porteous bullfighting as far south as LA county. There is an area which will have both put in, but that’s been kind of dying off for the past few years.

Anne Kelly (22:12):

So I was looking into this a little bit earlier, bull fighting. So the, the bloodless bull fighting specifically is what you’re looking at. Cause, um, I guess standard bullfighting, if you want to call it, that is, is illegal pretty much everywhere with the exception of Spain and Portugal at this point.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (22:33):

Yeah. So most people know in both flooding would be, which again, ignorant me. Um, 2009, I was in Spain and sort of gorgeous, beautiful arena. I’m like, wow. And I was like, and there’ve been still bullfight. Hadn’t really thought through it. And it’s like, we’ll fight tonight. I’m like, oh, okay. Like five years. Sure. I’ll come, come back at seven. I’m like, awesome. And I was like, wow, this is intense. So it’s like super intense. I’m like, okay. Was there mentally prepared for that? Um, wasn’t really into it. Um, didn’t really think about it. And then like a couple of years later, whatever they’re talking about it becoming outlawed in Barcelona and Catalonia. So I’m like, wow. I’m like Princeville has bull fighting. I’m like, is that going to get like eventually is going to go away? Like, is that part of my culture that I haven’t really explored?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (23:22):

That’s eventually not going to be around. Like if we have kids one day, are they going to know anything about this or whatever? It’s like, it’s already a dying sport, but like, I dunno, then they realized I didn’t really know anything about it. Uh, so in Portugal, so in Spanish bullfighting, yeah. You know, the Matador who fills the bowl on foot gets the passes, whatever, and eventually kills the, both the sport with the sword and Portugal. There’s no killing of the bull, but they do use when the dealers, you know, the things that they expect you on the back. Uh, generally, if the bull is a strong bull from my understanding is that that will get to have a very nice life, gets the breed and gets to enjoy itself. So in Portugal they actually fight on horseback. So the, if you look at them, they have like, uh, with period clothing and it’s kind of like nobility.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (24:05):

So if you, part of the King’s tribe or whatever, I’m totally in, that sounds great. But you would, um, have these beautiful, like majestic quirks that are from the loser Tano breed. They’re kind of like these war horses that were bred to be brave and to, you know, go to war and you would fight on horseback. Bullfighting was actually a way to develop those skills for battle and also to kind of show off those skills. And obviously you would be a well-to-do person at the time. You Swan in principle fight instead of being on foot, getting in the past, as he tried to get to those ones that he did on the back of, uh, of the bull, um, in California, again, decided to give, bringing your culture to a new place and then Morrison adapts to the local taste and laws or whatever in California they actually use.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (24:51):

And if you can see it, let me see if we could actually put like a Velcro strip on the back of the bowl. And then one that he actually have like a little Velcro tip. Um, so the both don’t get hurt, but it’s kind of interesting because unfortunately when they’re stabbing you with the thing, every time you, it’s your first time encountering a human in that way, every time you go up to the human, you get hurt. So you associate human pain, human pain here. You’re trying to get the human and it’s like, you tap me on the back. You’re just me off. So this Moses just getting more and more enraged throughout the fight. So in Portugal fighting still, then what’s the finale like that sounds kind of boring. So the finale is a symbolic hill. So you have the COVID laid on the chorus.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (25:33):

And then the finale, you have the group of eight men. Um, there was a group of women for condos in Portugal. Um, and the idea is it’s symbolic kills. So you try to get the bolts to charge you and you try to wrestle it to a standstill and that’s a symbolic kill. So if you can wrestle it with your hands, without any protection, other than your friends, that’s the end of the fight. It’s the symbolic kill. You try to get a tool quick, like at the end, you know, you wrestle it to a standstill. So you line that up and he try to get the bolt to come after you. So if you don’t get it on the first try, you usually have to do it a few times and think humans get bloodied and the bowl. So it’s bloodless for the bull, but not for the humans. So you should try to get the bowl. Um, and they represent like, kind of like the Portuguese cowboy, like with the workers. And they’re the only group of bullfighters that actually fight, um, as amateurs. I mean, they get bloodied, concussions, broken, whatever

Anne Kelly (26:29):

The fact that it’s bloodless for the bull, but not necessarily for the Matador’s.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (26:35):

Yep. And, um, it’s really interesting because it’s like the I’m really interested in the for cutter groups. I mean, that’s a great kind of get, because it’s like you’re taking the most risk. You’re the ones who are actually getting hurt. The guys on the horses rarely get hurt. Right. And it’s like, you’re an amateur. A lot of them are undocumented or don’t have insurance. It’s like, why are you willing to risk everything? And something that you’re really likely you’re going to get hurt. And some people can get hurt pretty badly. And it’s like, that’s what I’ve been kind of trying to figure out on this project is trying to get to that kind of like, why don’t you do that

Anne Kelly (27:10):

In my reading up on bull fighting earlier, I, I ran into kind of the origin of bullfighting actually had to do with a worshiping the bowls, but then sacrificing them, which kind of, I mean, not to say it completely put it together for me, but I guess when you think about when the bowl did inevitably end up dying within the fight was actually kind of a sacrificial event. It’s pretty wild to think about. I got to say,

DANIEL GONÇALVES (27:43):

It’s interesting. It’s kind of like what these do in the gladiators and all that. It’s like, what’s that it’s kind of like man versus beast thing, like again, masculinity versus vulnerability, right? Like you’re being masculine, but you’re going to get your kicked. Um, even like the clothes it’s like, it’s very masculine and then it’s like, you’re wearing tights or you’re wearing like, you know, lace and stuff. It’s quite interesting. Like, again, I’m just trying to understand it. I’m not trying to judge it or whatever. There’s a lot of respect for the animal. Like for the bull. It’s kind of interesting. Like, cause I guess going into a month monthly, just trying to kill these things, there’s just kind of like this barbaric thing and maybe it is maybe it’s not, I don’t know, but it’s like, I feel like there’s a lot of respect for it.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (28:20):

Like the ticket very seriously, the respect of the animal. And it’s like, it’s a sacrifice, but it’s like this kind of unfair fight, I guess. Yeah. You’re training your whole life and encountering for the first time. So, but the bowl also can tell you quite easily as well. And if you’ve, you know, those are really smart animals and they kind of figure stuff out really, really quickly. And that’s why they only fight once because they’ll figure stuff out very quickly. And it’s like this dance, like a lot of them over Fritz was like this dance or this ballet thing where they’re kind of like dancing with this beats. And it’s like kind of this beautiful thing. It’s very spiritual for a lot of people too. Like in, in California, it’s legal because it’s tied to religious ceremonies. A lot of the book fighting, they have an in Portugal, but a lot of it here in California, a lot of the immigrants came from the ASRS specifically from Ireland college CEDA when they came here on like the fifties or whatever, they started bringing their traditions and all that.

Anne Kelly (29:12):

Um, but yeah, just in kind of thinking about the worship and the sacrifice, just how you were talking about how the bowl was highly regarded, that, that aspect of it, it seems like hasn’t been lost

DANIEL GONÇALVES (29:25):

For me. It’s not about getting the prettiest picture or whatever for me, it’s like, how can I spend enough time with something that I might not agree with? Respect to come up with a, from something, some deeper understanding of other human connection with someone. And it’s like, and how do I share that with someone else? Like, that’s what I’m interested in. Otherwise it’s like, anyone else can take that picture. Like for me, it’s about that relationship that I have with that person or that group. Cause it’s like, that’s what I can contribute. I’m not going to contribute to the best golf planning picture in the history of both biting, but I can hopefully show you something that you’ve never seen before or feel something that you might not have felt or maybe something in their eyes that is unexpected in your own. Kind of what you think about something

Anne Kelly (30:09):

When, um, when the world opens up again, is there somewhere you would want to go specifically photograph both lights, Make it even more fun? Not only can you travel, but you can travel back in time. Well,

DANIEL GONÇALVES (30:29):

True truth. The boring answer. And I’ll wait for your order of the boring answer is actually would just rather just photograph what I’m photographing now. Like that’s what I’m

Anne Kelly (30:38):

Interested in. That’s perfect.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (30:40):

But the fun answer would be like, it it’d be fun to go photograph, like where, how many whales watching, you know, the bull fights in Spain just like hang out with him and photograph and kind of get his perspective on it before he wrote his book.

Anne Kelly (30:54):

So while we’re time traveling, if you could just time travel just for fun, for any reason, is there a place time and bull related that, that you would pick

DANIEL GONÇALVES (31:11):

We’ve really quotable back and see my parents like my age and like just kind of hanging out. It was kind of like, I don’t know, just recently I started kind of thinking of them as like humans as opposed to like parents. So we kind of just kind of cool to be like, what were you like at my age? Like, what were you into? Like, what did you do and how did you talk? And like, what was it like Kevin needed as a kid or something? You know what I mean? Like, I dunno, that’d be really cool to just kind of see your parents that your age.

Anne Kelly (31:40):

Yeah. So, I mean, maybe you kind of answered that, but if you were going to do that, would it be more, um, back to the future style where they didn’t know who you actually were? Or would you want to be able to introduce yourself as Daniel of the future?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (32:02):

Interesting. Cause if you do, Hey dad, what’s up. It’s like coming over from the future, then he’d be like, am I going to have my hair still? Like what’s going on? Right. Like tell me what’s coming. You know what a lottery numbers, whatever.

Anne Kelly (32:16):

And then you maybe convince them you’re not crazy. And I don’t know. Versus if you just show up as, um, I don’t know, some other guy wanting to have a beer or something then.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (32:29):

Okay. I think that would be cool. Cause then it’s like, you’re also not guarded. Right? It’s like, you don’t want to like, what, what am I, you’re my future kid. Like, I don’t want you to see me doing this thing. I’m not supposed to be doing. Yeah. Like a coworker. Like my, my dad was a waiter at a bunch of restaurants in Toronto. Like yeah. Just be like a fellow waiter that goes to the bar afterwards, like has a drink with

Anne Kelly (32:48):

Right? Yeah. You’re the new guy I’ve asked a lot of traveling questions and I’ve just recently started thinking about time travel because I don’t know.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (33:01):

Cause there’s no travel.

Anne Kelly (33:03):

There is no travel. So while we’re imagining travel, why not make it time travel?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (33:12):

Why not? Like we might have to them. It feels like we’ve still got some time to wait. Hopefully not too long. I know you’re mentioning about going to Portugal. Hopefully you were planning for next year, but maybe the year after,

Anne Kelly (33:24):

We’ll see how that all, how that all works out. I do have a cousin who is Liz living in Lisbon right now and another friend that lives in Porto. So I was hoping to go and 20, 21, but I don’t know. That might be a little, a little soon in, in this past year. And have you rewatched any old favorite movies recently that, that stand out to you?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (33:50):

Ooh, I’ve got to go on for you. And that kind of knew a movie related quick. She was coming up. Cause I have a watch here that shows if you haven’t watched it. And if you’re interested in the bull fighting thing, it’s called Gord, G O R E D. Um, it’s a documentary if you don’t watch it. It’s incredible. I probably watched, it seemed like maybe six or seven times. I’ll probably watch some Netflix, uh, that are prime. I’m not sure it’s one of those. Um, if someone, one of those, it’s just really good. It’s a beautifully done documentary, uh, something I’d aspire to do someday. Just it’s a bull fighter. Who’s like got a wife and kid. And so it talks about like how I got to go find him through him and his wife and it’s just really beautifully done. And it kind of really goes into like explaining this kind of passion.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (34:35):

It’s kind of one of those things where I’d watch it. Like before I got into this bullfighting thing, I had a different meaning than it does now. Like gonna watch it as I’ve been photographing this, I kind of watched it to like every year or whatever, a few months or something, I’ll kind of watch it again. It almost has like a different layer of like heaviness to it. Every time I see it, I feel like I understand a little bit more of where it’s coming from. Because again, it’s like, you’re like, what are you doing? They’re like, you’re crazy. And then you can kind of really start to understand that I’m like a little bit of straight getting more of a glimpse of like, okay, I get where this guy’s coming from. Like crazy in many ways, there’s this kind of like, it really feels like that intensity again that prepare, you know, the before and the after and things, diabetes and all that stuff.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (35:19):

Um, that’s a really good one. And um, if you’ve ever heard of the 66, 66 scenes from America, um, everyone is kind of famous recently. Um, you know, the Warhol Superbowl commercial, where he’s like eating the Whopper for like two minutes. I don’t know if you’ve heard of this, but I was like this whole thing where he eats a hamburger, he just eats a hamburger, like very, but the now thing, but it’s like these 66 scenes of Americans probably filmed in the eighties or nineties or whatever it was and um, really cool documentary too. I really liked that too. What kind of older stuff?

Anne Kelly (35:53):

That’s I really think that, that, um, anything that kind of stands the test of time is kind of that next level. So, so how about music when you are? Um, I guess probably when you’re out shooting photos, you wouldn’t be listening to music cause that doesn’t really make sense. But when you’re editing photos, is there, is there a soundtrack to that?

DANIEL GONÇALVES (36:18):

It depends. Um, we have like the local NPR affiliate called KCRW in LA, but I usually have that on, I don’t like house music or whatever. Just kind of cool, like kind of a bit more Transy kind of stuff with Chile, but yeah, I don’t know. Just kind of, um, recently I’ve been listening to like a lot of like fifties music and stuff obviously cause the Elvis and stuff. So it kinda like been kind of digging at that time. Frank Sinatra, stuff like that. That’s been kind of fun. I fired him as we were talking about before that was sent to that, because that kind of speaks to the bullfighting experience, I think,

Anne Kelly (36:49):

Which is basically Portuguese, um, blues, as you had kind of explained it.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (36:55):

Yeah. So in, um, Lisbon, I don’t know how to get this magic pen. Uh, Elizabeth, um, it’s usually some by women. So traditionally it’s usually like, you know, some lover loss or some somebody who died or whatever. It’s like very kind of gut wrenching, Brita, emotional, like very strong visceral, like singing. It gives me goosebumps even thinking about it.

Anne Kelly (37:20):

You, you had sent me a few links sometime ago when you had introduced me to it. Are there a few particular musicians in that genre genre that you would suggest people check out

DANIEL GONÇALVES (37:33):

The original, the original OJI? Like the one model? That’s the one that’s that’s where you start and stop. I mean, it seems like because the original she’s the eldest Iraq mural. She’s the eldest of 5 0 1 and she’s yeah. It’s it’s like you can’t not listen to her. And then like just not get goosebumps, like every few seconds it’s just chilling. Right? It’s this beautiful chilling. And I’m also experimenting with, um, we’re talking about [inaudible] leaves again, one of these examples of something that, you know, started off in the island of Madeira, you know, the people came from the Azores to Hawaii and then different people play with it and then became a different instrument that resembles the original. But now it’s called the Uka lately. So I’m like kind of trying to learn how to play that very unsuccessfully, but I’ve been kind of,

Anne Kelly (38:19):

And as you know, this wouldn’t really be art in the raw. If I didn’t ask you, if there was anything that you collect,

DANIEL GONÇALVES (38:30):

When we travel, we get little pennies. You’ve ever seen those little pennies that they eat, like put a penny in like 50 cents and you crank the machine. She was like a little penny passport. We have a few of those that we’ve been collecting over the years. Every time we see one get really excited. Cause you don’t see them very often. So we have those. Sometimes we have like double all the same thing because we forgot like WebEx or Cedar, like the penny machine. I was like, I already got this one pictures. Obviously our books, books. I love photo books, my photo publisher, friends and Chris graves and Sitara and so many like good people doing good work and

Anne Kelly (39:08):

Well, thank you so much for joining us tonight, Daniel and thank you everybody for listening. If you like the conversation, please like comment, subscribe. As I’ve been saying, keep the conversation going and Daniel, before we say goodnight, tell everybody your last name again, because we’re going to get this through everybody’s head.

DANIEL GONÇALVES (39:34):

We’ve gone slaves. It’s all this guns. All of us are going to salvage. If you want to really be proper.

Anne Kelly (39:45):

Well, I’m going to eventually try and get download the proper Portuguese pronunciation. I’ll work on it anyways. Well, thank you so much and have a great night. And um, we will talk soon. Yes. In Santa Fe forever. Portugal’s Santa Fe meet and Santa Fe flight to Portugal, something like that. Have a good night.

Speaker 3 (40:30):

[inaudible].